As the celebration of the sesquicentennial of science comes to a close and the one-year anniversary of Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C.’s passing approaches, the University of Notre Dame reflects on the life of Father Hesburgh and his impact on the growth and development of the sciences and scientific research at the University during his tenure and beyond.

Hesburgh served as president of the University of Notre Dame for 35 years, from 1952 to 1987. During this time, Notre Dame grew in significant ways: doubling its enrollment, growing its endowment from $9 million to $350 million, and opening its doors to women. In addition, during the approximate 35-year period of Hesburgh’s presidency, research awards grew from $2 million in 1955 to $29.8 million in 1988. On this solid foundation, Rev. Edward A. Malloy, C.S.C., who was president of the University from 1987-2005, increased endowed faculty positions to more than 200. During current president Rev. John I. Jenkins, C.S.C.’s tenure, research awards have grown to record-breaking levels, reaching $133.7 million in Fiscal Year 2015.

When reflecting on Hesburgh’s presidency, Jenkins said, "Inspired by our founder’s vision of Notre Dame’s inevitable greatness, Fr. Hesburgh embraced faith and the sciences to help build an unrivaled undergraduate experience and to pave the way for Notre Dame’s future role as one of the world’s great research universities.”

Inspiration and Legacy

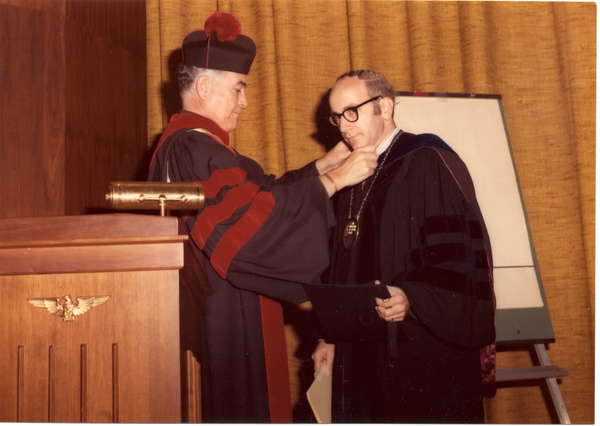

One of the significant academic contributions that Hesburgh is known for was the creation of the endowed professorships. This program brought George B. Craig, Jr. in Biology, James L. Massey in Electrical Engineering, and Anthony Trozzolo in Chemistry, to the University as part of the first cohort appointed by Hesburgh. Anthony M. Trozzolo, C. L. Huisking Professor Emeritus of Chemistry, worked alongside Hesburgh for many years, joining the faculty of the College of Science in 1975. As Trozzolo recalls, Hesburgh was inspired by a speech that his predecessor, Rev. John J. Cavanaugh, C.S.C., gave where he challenged the Catholic academic community by saying, “where are the Catholic Einsteins, Oppenheimers, or Salks?” Trozzolo shared, “I think it certainly made an impression on Fr. Ted, because I think he felt that challenge was one that he was destined to play an important role in.”

Trozzolo reflects on his period as a faculty member in the sciences under Hesburgh’s presidency in a new video. To watch the video, please click here.

Hesburgh supported the need for advancement in the future of science and technology but felt that “the answers will only come if scientists and engineers put their science and technology to work in the true service of mankind everywhere.” He lived this commitment day-to-day, serving on many global scientific committees and boards, also receiving a major scientific award, including:

- The National Science Foundation, 1954-1966: He was appointed by President Eisenhower, this first of his 16 Presidential appointments.

- International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), 1957-1970: Hesburgh served as the Vatican City Permanent Representative to the IAEA.

- United Nations Conference on Science and Technology for Development, 1977-1979: Hesburgh served as the U.S. Ambassador and Chairperson of the U.S. Delegation.

- The Rockefeller Foundation, 1977-1982: Hesburgh served on the board and as Chairperson.

- National Academy of Sciences, 1984: Hesburgh was recognized by the American scientific community with a Public Welfare Medal for his “deep understanding of the importance of science in the contemporary world and his effective advocacy of the application of science and technology in dealing with critical societal problems.”

- Many others, including the Nutrition Foundation Board, the Policy Advisory Board of the Argonne National Laboratory, and the Board of the Physical Science Study Committee.

In each of these roles, from serving as a “champion of the social sciences” to helping to solve a global hunger crisis, Hesburgh believed that “being right at the heart of all the basic scientific discussions and decisions” while with the National Science Board “really changed [his] life” and he applied these learnings and inspirations back home at Notre Dame.

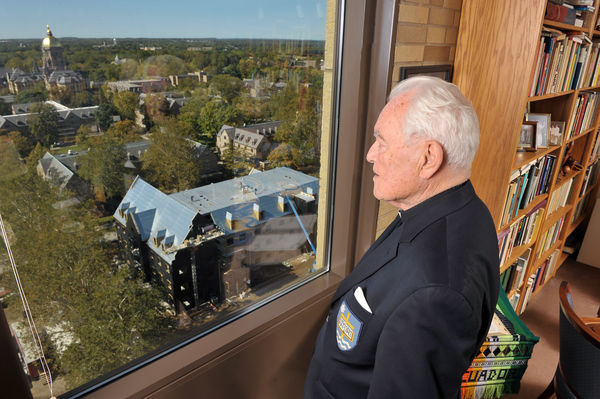

On campus, Hesburgh remained committed to growing the University, as well as the sciences, in a myriad of ways. From the dedication of the Nieuwland Science Hall in 1953 to the opening of the Radiation Laboratory in 1963, some of Hesburgh’s earliest successes in the sciences were related to upgrading, expanding, and building much-needed facilities at the University. Also included in the 40 new buildings that were built when he was president were the Galvin Life Science Center (1972) and Stepan Chemistry Hall (1982).

“With the recent development of our world-class shared research facilities and the new 220,000 square foot research building, McCourtney Hall, which will enable collaborative research in molecular sciences and engineering, drug discovery, and materials science and engineering, Notre Dame continues to be inspired by and grow within Father Hesburgh’s grand vision for scientific research and discovery at the University. Our faculty and new faculty recruits continue to be inspired by the Notre Dame mission of being a powerful force for good in the world and in the sciences,” said Vice President for Research Robert J. Bernhard.

Trozzolo reflected on the development of the science facilities during this period, noting that they had “a role in attracting people” to Notre Dame. Hesburgh was keen that people knew what was happening at Notre Dame so that the University would continue to attract excellent undergraduate students, graduate students, and faculty. As part of this awareness raising, Notre Dame celebrated the Centennial of Science in 1965, recognizing the 100th anniversary of the founding of the College of Science and the awarding of its first Bachelor of Science degree. This year-long celebration brought together great minds from across the country and even prompted President Lyndon B. Johnson, who also awarded Hesburgh the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest honor, to write him and say, “Today America is preeminent in science and its applications…in this scientific renaissance the University of Notre Dame has played its part as a foremost Midwestern center of science and learning.”

Hesburgh’s enduring legacy exists in programs of research at the University that continue to this day. Some examples of programs that began during Hesburgh’s tenure include:

- The Vector Biology Laboratory (VBL), 1957: Established by George B. Craig, Jr. and a now a strength of the Department of Biological Sciences and the Eck Institute for Global Health, the VBL became a world-renowned research program in mosquito biology and genetics where, at the time, 80 percent of all genetic research on Aedes aegypti in the world was conducted at Notre Dame.

- The Laboratories of Bacteriology, University of Notre Dame (LOBUND), 1961: Here Notre Dame researchers pioneered the techniques necessary to produce and rear germfree animals, which are essential for immunology, bacteriology, and other biological sciences research; this work continues today through the Freimann Life Sciences Center.

-

University of Notre Dame’s Environmental Research Center, 1968: An 8,000-acre pristine wilderness on the boundary of the Michigan-Wisconsin border, providing the opportunity for year-round field ecology research, with a focus on forest, aquatic, insect, and vertebrate ecology research, in a location protected from human disturbance.

“Fr. Hesburgh’s impact on science at Notre Dame and in the nation was tremendous and continues today,” said Mary Galvin, the William K. Warren Foundation Dean of the College of Science. “It is a privilege to be able to build upon the solid foundation he laid. As Fr. Hesburgh recognized, science and the knowledge it discovers are critical to solving the challenges we face in global health, energy, the environment, and sustainability.”

Continuing Celebration

As Notre Dame turned the calendar page on the celebration of 150 years of science at Notre Dame and now reflects upon the one-year anniversary of Fr. Ted’s passing, Hesburgh’s own words still ring true:

“May science ever feel at home and relevant to all these truly human concerns here at Notre Dame and may the second century of science be marked by a giant step forward, wherein the great realities of the universe are better understood and better managed for the growth of scientific knowledge, for the good of mankind everywhere, and for the glory of God, too.”

- Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C., 1917-2015

Originally published by Joanne Fahey at research.nd.edu on February 22, 2016.

Originally published by Joanne Fahey at research.nd.edu on February 22, 2016.